A PhD writing survival guide

After having had some time to reflect on my writing process I’d like to share some of the things that I found useful during the writing of my PhD thesis. There’s probably already a million of these articles out there, but this also means that one more shouldn’t make much of a difference, so here we go. In principle this should all be applicable for other thesis writings as well. But this is obviously a personal thing and colored by survivorship bias. So take it with a grain of salt.

Setting up a Project

Before writing a single sentence I spent some time setting up a project workflow that worked for me. I chose to set up a Git repository, in order to have fixed commits every time I made major changes during the writing. While Word’s docx files are all but useful for running a git diff on, it still has big benefits: Being able to roll back to a given commit not only avoids having a million chapter2_v3_final.2.docx which can only be differentiated by the edit dates, it also beats the nameless versioning of Dropbox et al. If you set up your repository on GitHub, you even get a free offsite backup. And people who (foolishly 😂 ) volunteer to proof-read your writing can just make a new branch to write their comments without having to worry about making destructive changes to your writing. If you don’t feel like having a public repository for your thesis: The free GitHub Student Developer Pack comes with unlimited private repositories, just register with you university email address.

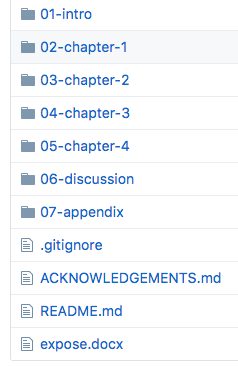

For the actual writing I chose to subdivide the whole thing into subfolders in my Git repository, having a folder for each chapter. For me this was a big help in keeping track of which chapters were already drafted/edited/etc. and to get a sense of how much was already done. Each chapter’s subfolder also got their own figures/, tables/ and sometimes analyses/ folder. This makes it much easier to keep track of where the individual raw figures/tables are located in case you want to make some edits outside your word processor. I unfortunately did not end up using the analyses subfolders consistently. Having each analysis in their own YYYY-MM-DD-analysis-name subfolder is great to quickly go back to the data if the need arises and makes it super easy to later on compile the supplementary data. As I failed on that end it took me much longer than it should have. Having the data in your writing-repository also means that you have versioned data that’s backed up. 👍

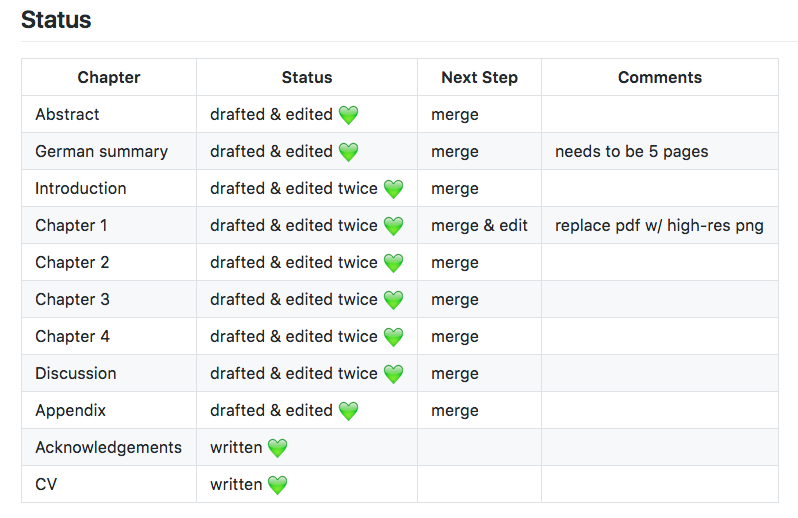

Besides the general folder structure I kept a general README.md file in the repository’s root. Besides giving an outline of the repository’s structure (to remind me of my own organizational ideas) I used it to keep track of what things are to do next and monitor the general progress of my writing. Having some files for note-taking (like the ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.md) is also useful for collecting the things that go around the main content.

Outlining

With the project all set up it’s time start the actual writing, right? Nope. Setting up your project folders already requires you to have some idea of what to write in each chapter, but for me it was an additional help to write individual outlines for each of the chapters. For that reason I put an additional README.md into each of the chapter’s subfolders. Under the time-tested headlines of Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion and Outlook I planned out the general writing for each chapter: which things to highlight in the introduction, which results should go in, what to discuss in the end, and how to get a segue to the next chapter. Having this already put down somewhere was a big help for me, as it was a great cheatsheet for the things you ultimately want to write down. It is also a great way not to get lost in the real writing that’s to follow.

The Writing

Okay, there’s no way to sugar coat it: This one is a drag. It takes a lot of time and – at times – is not the most exciting thing to do. For me it felt like I spent days just staring at the screen and all I got done in the end was half a page. Often that is because Perfect is the enemy of good is what you’re up again. I often had to remind myself that getting an imperfect first draft is better than not having written anything at all, as it’s generally easier to edit than write from scratch.

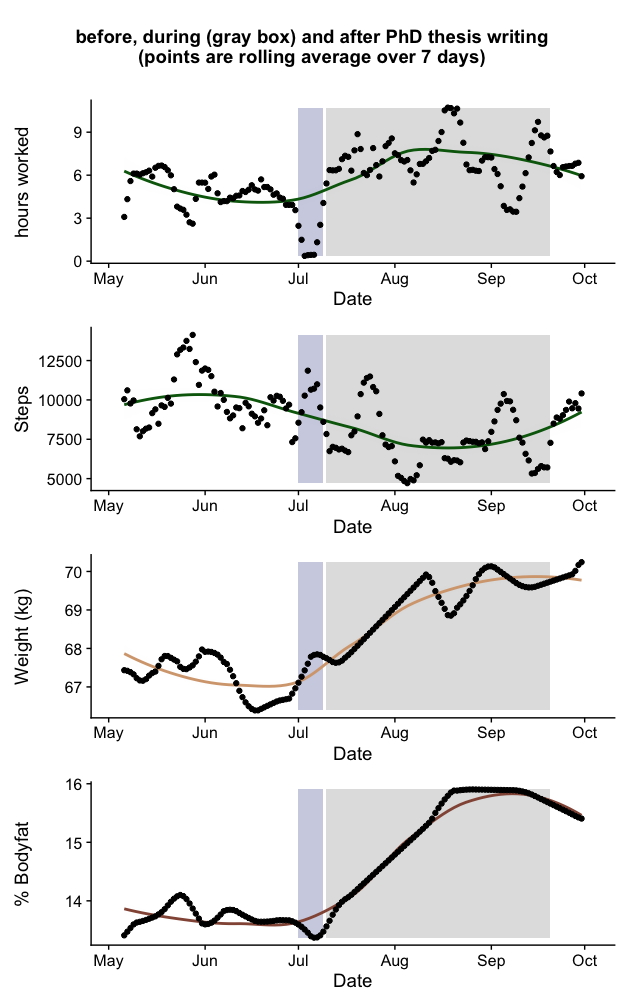

With the writing come the secondary effects, especially if you’re operating under a tight deadline. For me that meant spending significantly more time in the office, including the weekends (see this post for a more detailed breakdown of it). This also means less social interactions and less physical activity (see my weight gain in the graphs above). Both can easily take their toll on your mental well being, they certainly did for me. Thus, take breaks and get away from your desk. Meet friends, go outside, do whatever helps you to wind down. Track your progress regularly, so that you can tick of things from your to-do list and update your README.md with all the things you’ve already achieved, that was a big morale boost for me.

Some other assorted things that I found useful or learned while writing up:

- Don’t spend too much time on getting the typesetting/formatting done right from the start. This will most likely change during the writing in any case. This is especially true when using Word et al. over LaTeX.

- While LaTeX loves

.pdffigures, Word hates them, downsampling them to something that looks ugly. Perform the conversion to a pixel graphics (e.g..png) yourself and add the figures then. - Learn how to use the cross reference feature of your writing tool. Being able to quickly set a see Figure 4, page 232” saves you a lot of time.

- Use a reference manager that has a nice integration into your web-browser and your writing tool of choice. I used the Mendeley Desktop client along with their Chrome and Word plugins. This makes it easy to add a new reference right from the journal website to your library, as it will (most often) correctly identify all meta data. It also makes citing things in your editor super easy.

- While the browser plugins are cool, check what they add to your library: I frequently ended up having the same person listed as “Doe, John” and “Doe, J” in different publications. This leads to the full first names end up in your (Doe 2008) citation styles.

Backups

I feel no text about how to write your thesis is complete without mentioning the issue, preferably a number of times. So yes, do backups. Your hard-drive will suddenly die, a fire destroys the office, you lose your computer on the train, the cat pees into your notebook. Whatever it is, you don’t want to lose your hard-fought-for writing progress. Putting your writing in a (private) GitHub repository is good, having your files on Dropbox (et al.) as well. Doing regular backups of your own computer is something you should do in any case (if you’re on a Mac TimeMachine works reasonably well for that). I tend to be a bit paranoid about those things, so I ended up having basically all of it: a GitHub-synchronized repository, with the current working copy synced to Dropbox, in addition to two TimeMachine-backups, which were stored in physically separate places, assuming that if all of this fails to save my data I will have different worries than finishing my thesis writing.

tl;dr

Writing any thesis takes a lot of time and energy. Having a well-layed out project repository helped me a lot to structure my month-long writing process. Nevertheless it literally weighed me down. Being able to track and see my progress was a great motivator to pull through despite that. Oh, and make backups!